Wilfred E S Owen MC ~ The Principle of the First-Person Narrative

The Great Poets

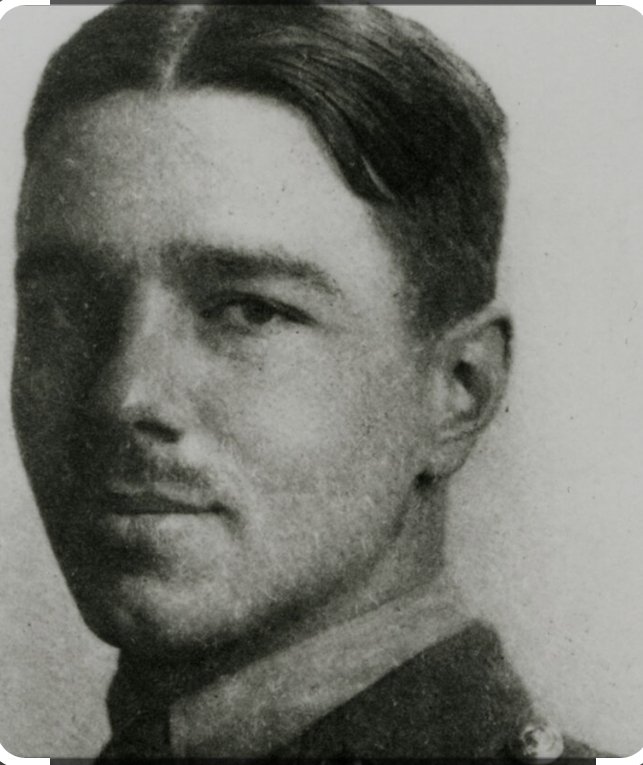

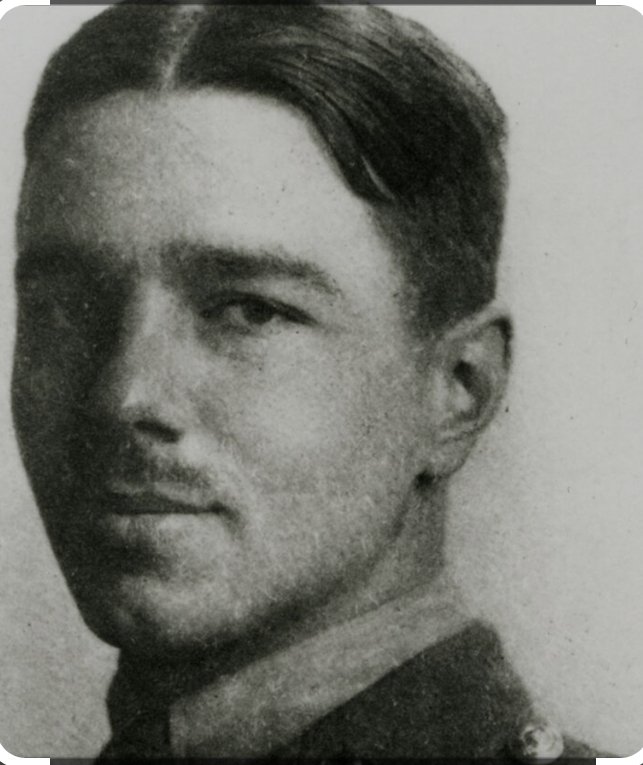

Wilfred Owen MC

The Principle of the First-Person Narrative

On 2 February 2024, late in the evening, reading the biography by Jon Stallworthy, I was obviously reading it in the third-person narrative. That is how we read most works.

The biographer is the conduit, I prefer to say the bridge, between the person whose biography I am reading and me, the reader.

I pondered. That is excellent. I have learned so much from Stallworthy. I paused afresh, poured myself a glass and wondered how the passage would read as if it were Owen himself talking to me, explaining to me his methodology. How would it sound? Would it resonate? Would I be correct to do this?

A sip later, I copied the narrative from pages xix-xx, moving it from third-person to first-person, imagining that I am a student in Wilfred Owen’s class. He was, after all, a teacher before becoming a soldier.

First-Person Narrative

(From Jon Stallworthy’s Third Person Narrative)

My readiness to express my feelings of grief, tenderness, delight, as well as indignation, is a significant part of my appeal. My readers are often moved by the immediacy of my work before they appreciate the subtle density of its literary illusion. So, too, with its music.

In February 1918, I told my cousin Leslie Gunston: “I suppose I am doing in poetry what the advanced composers are doing in music.”

I regarded myself as being apprenticed to Keats and Shelley, I had absorbed the traditions of harmony and rhetoric that they inherited, and then extended. The harmonic tradition that I extend with my pioneering use of “para rhymes - escaped/scooped, grind/grounded… Are two examples…

In “Strange Meeting” from which these examples are taken, you will see, my friend, that the second line is usually lower in pitch than the first, and I do this to give the couplet “a dying fall” that musically reinforces my poem’s meaning; in this case, it is the tragedy of the German poet (in one of my manuscripts), you will see that I have written:

I was a German conscript, and your friend’, his life, being cut short by the British poet, whom he meets in Hell.

In my poem “Miners”, I caused the pitch of the pararhymes to rise and fall, as the sense moves from grief to happiness and back to grief again.

So, let me show you this in the following stanza:

The centuries will burn rich loads.

With which we groaned,

Whose warmth shall lull their dreaming lids,

While songs are crooned.

But they will not dream of us poor lads,

Left in the ground.

This same poem, my friend, offers an example of something else I introduce ~ harmonic innovations.

What do I mean by harmonic innovations?

Simply this. The punning, internal rhyme of “why (…), Writhing“, found also in the “men (…) Many “of Dulce et decorum est.

What finally sets me apart from all, but my most major contemporaries, however is a breadth and depth of vision that you will find in Futility, for example, in which I can hold, as it were, in the palm of my hand, the grand, and the granular together:

I will show you this in two stanzas, but let me just make this one remark before I do so. In short, my loyal friend I see you doing something similar in some of your poetry, even though you are not aware of it, and an example is “QUANTUM LEAP” and which you have now developed, and given it, its better title “from death and back to life, a quantum leap “.

The two stanzas I referred to above, are here:

Move him into the Sun –

Gently, its touch woke him once,

At home, whispering of fields unsown.

Always it woke him, even in France,

Until this morning and this snow.

If anything might rouse him now

The kind old sun will know.

Think how it wakes the seeds –

Woke, once, the clays of a star.

Are limbs, so dear-achieved, are sides

Full-nerved, still warm, too hard to stir?

Was it for this the clay grew tall?

O what made fatuous sunbeams toil

To break earth’s sleep at all?

So, in the larger meditative structure of “Insensibility”, I can move with no loss of tension from the colloquial to the cosmic, from “poets” tearful falling to “the eternal reciprocity of tears “, a phrase that, dare I say it, even Shakespeare might have envied.

End of the First-Person Narrative

All I have done here is to write that which we do subconsciously when we listen to our favourite songs.

I often do this with my own work. If, for example, I have a poem or story in which I have created several or half a dozen characters, I will then at different times assume the mantle of one character, reading the poem or story from that character’s angle; it is as if I have become that character’s personality, mindset, sexuality, voice, accent and being.

I always learn so much more by doing this, and when I do this with the books I read by writers, poets and playwrights, my whole world changes.

It is as if I glimpse the shoes of that person, and fleetingly, try them on.

6 July 2025

First written on 29 June 2024

Eros inspired by Wilfred Owen’s Sonnet ‘To ‘-’ London 10 May 1916’

Ken Webb is a writer and proofreader. His website, kennwebb.com, showcases his work as a writer, blogger and podcaster, resting on his successive careers as a police officer, progressing to a junior lawyer in succession and trusts as a Fellow of the Institute of Legal Executives, a retired officer with the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, and latterly, for three years, the owner and editor of two lifestyle magazines in Liverpool.

He also just handed over a successful two year chairmanship in Gloucestershire with Cheltenham Regency Probus.

Pandemic aside, he spends his time equally between his city, Liverpool, and the county of his birth, Gloucestershire.

In this fast-paced present age, proof-reading is essential. And this skill also occasionally leads to copy-editing writers’ manuscripts for submission to publishers and also student and post graduate dissertations.