We Know It As The Great War ~ You Know It As The First World War

We Know It As The Great War ~ You Know It As The First World War

An aspect of a BE2c Royal Flying Corps

I am also an observer/photographer, fortunate to have joined the RFC shortly after cameras were introduced.

My task is to assist the artillery. When our heavy guns open up, the gunners need our eyes to tell them where the shells are landing, so they can correct the range and direction.

In decent weather, I can usually see where a shot is falling, but at the start of this war, there was no efficient way of communicating this to the ground until 1916, the year I transferred from my regiment to the RFC when some aircraft capable of carrying radio transmitters came into service.

Truly state-of-the-art.

I combined the use of radio with the “clock system“ which is a code of number and letter coordinates that identified where a shell had fallen in relation to the target, and this was reasonably efficient. But the first Battle of the Somme 1916, was static warfare, and artillery simply could not deal with the very deep underground fortifications that interlocked the German trench lines.

Feldwebel Ernst Dachbauer aus Koblenz in Rheinland-Pfalz in 1919.

Kadett Friedrich Hirt von der Düsseldorfer Reitschule in 1920

It is 1918 and we know that the war is coming to an end. It is almost November and there is no way that we could go through another winter on the Western front. Any of us. All sides.

I serve with the Royal Air Force. It used to be the Royal Flying Corps. There is some delay on our new uniforms and ranks, hence the RFC is a real hotch-potch of khaki, blue, whatever.

I am an observer/photographer. Do not assume that “state of the art” only relates to your age in the 21st century. We have state of the art too. Let me explain. In 1915, I would sketch and make notes high up in the sky as a technique for aerial reconnaissance. Then we introduced photography. These were unwieldy box cameras, but over many flights, many days, weeks even, they would gradually build up an exact picture of the enemy’s trench systems and gun emplacements. My work was ghastly, with freezing fingers operating in the gale of the aircraft slipstream, and we were flying at 20,000 feet (6,000 m). The loss rate was appalling but it was the price paid to build up comprehensive photomontages of trench systems, built up and used for selecting targets for the artillery.

You have a hint of this as you watch from afar, within the safety of your shores, the devastating War in Ukraine.

That is very true.

It is now 1918, and the battlefront is now far more mobile. The downside is that we have sacrificed thousands of airmen in an artillery-bombardment strategy that combines both the Allied Armies and their air branches, and for us Brits, our fledgling independent Royal Air Force.

Without our airmen, this bombardment strategy would fail.

I have a question.

If you’re a politician - whether now in 1918, or in your century in 2023 - how could you have allowed this war to ever happen?

You have blood on your hands, and your ballot papers and silly speeches are stained with the blood of millions of men and women and children.

May God forgive you, because I don’t, and never will.

My British friends are correct. It is now 1919, and the Versailles Peace Treaty has stripped us of everything, and I have an awful feeling that its intention to guarantee peace, and prevent a world war from happening again, will, in fact, lead to yet another, and even more ferocious world war.

I pray to God that I am wrong. I am very proud that in 1918, the German air force introduced the Rumpler CVII. This was revolutionary as it was fitted with an automatic camera, taking a series of pictures when triggered. We, too, flew at 6,000 meters.

The downside was the complete lack of protection for high-altitude flights. Many crews suffered from freezing cold because they were in open cockpits, with a lack of oxygen, and the consequent ‘Bends’. They would wear covering over their faces to try and minimalise frostbite.

Die Düsseldorfer Reitschule 1920

I leave the final word to a long-distant ancestor, Kadett Friedrich Hirt von der Düsseldorfer Reitschule im Jahr 1920.

Mittlerweile ist es fast zwei Jahre her.

Wir haben eine junge Demokratie, eine Republik – die Weimarer Republik, und wie mein Name schon sagt, liebe ich die Arbeit mit Tieren und der Landschaft.

Ich stimme meinem Freund Ernst zu.

Der Vertrag von Versailles ist verständlich, aber ich befürchte einen schrecklichen Fehler. Viele sehnen sich nach Militarismus und Autokratie. Meine Vorfahren und ich bewirtschaften das Land seit Generationen. Es gibt Frieden, wenn ich eins mit der Natur bin.

Mein Name bedeutet auch friedlicher Herrscher. Ich habe einen Nachkommen in Großbritannien, dessen Onkel ebenfalls Frederick hieß. Er wurde 1899 geboren. Auch er wurde in den letzten Tagen des Jahres 1918 vor dem Waffenstillstand getötet. Sie sehen also, es gibt immer eine Verbindung zu unserer Vergangenheit und wir dürfen niemals unsere Wurzeln verleugnen oder jemanden mit anderen Wurzeln bedrohen. Tiere bedrohen nie. Die Bedrohung kommt nur von der menschlichen Natur.

2 July 2023

All Rights Reserved

© 2023 Kenneth Thomas Webb

© 2023 Eyes to the Skies

Digital Artwork by Kenneth Thomas Webb unless otherwise stated

The Glosters

The Gloucestershire Regiment in 1914 after the outbreak of war.

Pte Frank Ewart Marshall 1914 aged 16

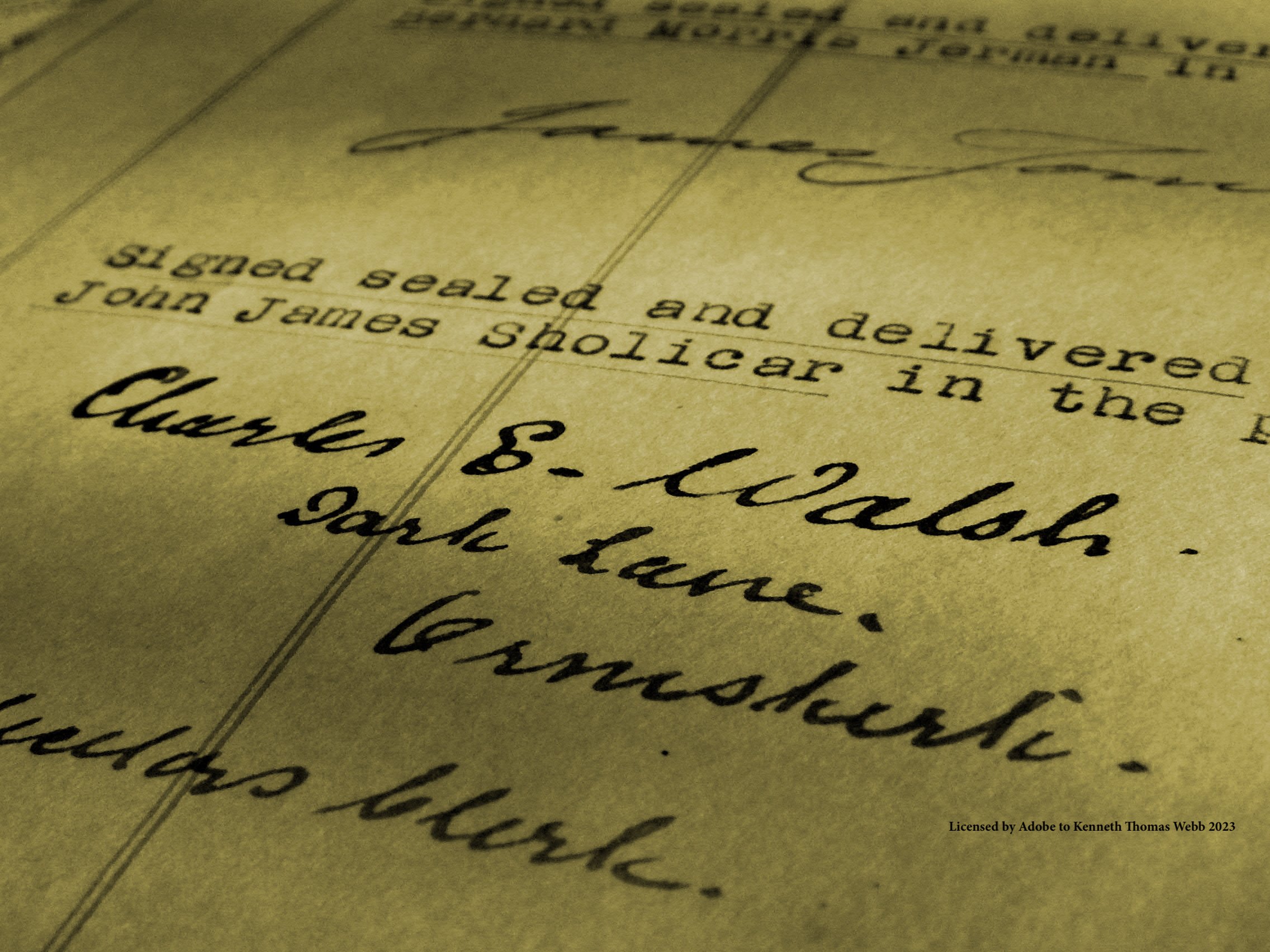

My maternal Grandfather served in France and was taken prisoner after a fierce battle that involved hand-to-hand fighting with the long bayonets that all sides used at that time. I report this in Windsor Street Days when, one day, Grandad decided to tell me about his service. Along with his brothers Frederick and Harry (Henry), all three volunteered immediately for service, and Grandad alone returned.

Pte Horace Albert Webb 1916

My paternal Grandfather served in the mechanised division as a driver, but due to his previous occupation as a coachman-chauffeur in Gloucestershire, his commanding officer requested that my Grandfather regularly exercise his Charger. This was, I imagine, the most welcome relief for Grandad Webb.

Ken Webb is a writer and proofreader. His website, kennwebb.com, showcases his work as a writer, blogger and podcaster, resting on his successive careers as a police officer, progressing to a junior lawyer in succession and trusts as a Fellow of the Institute of Legal Executives, a retired officer with the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, and latterly, for three years, the owner and editor of two lifestyle magazines in Liverpool.

He also just handed over a successful two year chairmanship in Gloucestershire with Cheltenham Regency Probus.

Pandemic aside, he spends his time equally between his city, Liverpool, and the county of his birth, Gloucestershire.

In this fast-paced present age, proof-reading is essential. And this skill also occasionally leads to copy-editing writers’ manuscripts for submission to publishers and also student and post graduate dissertations.