RFC 1 The Royal Flying Corps ~ An Introduction to the Fictional James Bigglesworth by Captain W E Johns

RFC 1 The Royal Flying Corps

An Introduction

2025

I’d enjoyed reading the Biggles stories as a boy in the early 1960s when they came out each Saturday in picture format; and very soon I moved on to the Second World War. Very quickly, the predecessor to the Royal Air Force faded into memory.

Finding this title on a visit to Winchcombe in March 2023, well, what a find.

Why so? Because the accounts had the feeling of being disengaged. Disengagement from a period of aviation history and interest spanning the years 1935 to the present, requiring me to recalibrate. Why had I overlooked the emergence of Aviation in all its splendour, its meteoric development, its rapid development as a method of serious travel and then its descent, in the hands of people, to a means of destruction and terror in just six years?

In doing so, what a world I find awaiting me between 1912 - 1918.

Not only sophisticated biplanes, but Balloons and Blimps ~ we now know them as Airships ~ as well as the advent of anti-aircraft batteries, the first searchlight batteries, the first London Blitz, and entire industries that are now a historical note only.

In short, I had been pulled up with a jolt.

In an Antiquarian Bookshop…

In a beautiful Antiquarian Bookshop in my local Cotswold town Winchcombe, a cover caught my eye…

Spellbound, I was eleven or twelve again…

Pulled up with a jolt, I was bewitched!

BackCover ~ BIGGLES of the Royal Flying Corps by Captain W.E. Johns (1978 Edition)

II

This is exactly the antidote to free up my mind again, to not make such stupid mistakes and errors of judgment, and to also get back into the business of enjoying life despite the restrictions with which we all labour, wherever we are in this beautiful planet.

Reading Biggles of the Royal Flying Corps by Capt. W E Johns has enabled me to understand a little more of the American Boeing Stearman Kaydett Biplane in which my father’s brother learned to fly, before transferring to the larger T-6 Texan monoplane (the Harvard in the Royal Air Force) in which he and his friends “got their Wings” in April 1942, and, for the short time that they remained in Alabama before shipping back to Britain in May 1942 on the treacherous Atlantic Convoys that required the ships to cross that mid-ocean known as the Black Pit - that area that was beyond air cover from the States and from the United Kingdom respectively; to proceed to their squadrons, permitted to wear the coveted USAAC Wings whilst on American soil, eventually in the equally coveted and highly respected SNCO rank ~ Sergeant-Pilot. Moreover, I find, a rank that has its root firmly embedded in the history of the Royal Fling Corps.

No wonder there was a very respectful whisper by all, regardless of rank, when a sergeant-pilot was part of the crowd. Countless senior officers in both the RFC and its successor, the Royal Air Force, had been sergeant-pilots, sergeant observers, sergeant engineers in the RFC.

Reader, I do not equate my uncles to the author W.E. Johns. I think Ken Webb would have something to say about that by way of gentle rebuke along the lines of thanks Ken, but get a grip, lad, and which would be echoed with gusto by Harry Marshall.

Captain Johns has opened up a whole new world of what it is like to fly a biplane.

They are beautiful machines.

Deep down I knew this, but now their beauty and engineering enables me to appreciate that they were state of the art in their day, in constant stages of development and improvement.

Captain Johns’ authorship also provides a much clearer and very important understanding of the Royal Flying Corps and its naval counterpart, The Royal Naval Air Service, and of the very brave people who served in both air branches between 1912-1918.

III

Several years ago, visiting our closest family friends in Essex, John (also retired RAF VR) took me to Maldon in Essex, the United Kingdom’s only remaining Royal Flying Corps station, now the Stow Maries Great War Aerodrome.

How strange. We can become so concentrated upon one aspect of a subject that we gradually, without realising, drift away from what we might call the overall picture.

That visit sowed the tiniest seed.

For a while, it was hidden from daylight by the discovery of the crash site of my father’s brother, a Handley Page Halifax DK165 MP-E (i) in dense woodland in Lachen Speyerdorf (1943). I have written separately about this and also of the crash site of my mother’s brother, an Avro Lancaster PB402 LQ-M (ii) also in woodland near Pffaffenhausen (1945). These were just two of the seventy-seven thousand RAF personnel killed in the Second World War, 55,573 of whom were from RAF Bomber Command.

Thus, when I first saw this book title in the Antiquarian bookshop in Winchcombe, it was akin to the pearl in the sand.

In the extract that follows - clearly written from the author’s own very direct experience in his own service as a fighter pilot with the Royal Flying Corps - the sands shifted. The portrait of my uncle sitting in or standing on the wing of the Kaydett made me re-evaluate everything.

I am ashamed to say that when I read this first novel, I was completely unaware, for example, of Lieutenant Albert Ball VC or of Major James McCuddan VC.

Spring passed into Summer, then Autumn, then Winter and now I find myself in late Spring 2024, holding that pearl hidden from light has now shining brightly. The searchlight of learning about the men and women of the Royal Flying Corps truly evaluates and works towards understanding the First World War, on the Western Front especially, where my mother’s father fought with his brothers, and only he returned, and the paternal side, my father’s father and brothers (and in-laws) all of whom fortunately did return. This merely reflects the price paid by all families in that war that was meant, they surmised with confidence, to end all wars.

In this regard, The World’s War, by Professor David Olusoga OBE, is a masterpiece.

At last, I am obtaining fresh and exciting perspective on everything, but often I hear the air raid sirens too, the sense of alarm that now, in 2025, we live at time time of extreme danger. Greenland, come to a deal or I might invade? Denmark, play ball or accept crippling tariffs? Canada, you need to be the fifty first state? And as I write we have yet to see the 47th Inauguration.

IV

However, let us close by return to this beautiful extract.

As one who has been privileged to wear the Royal Air Force uniform, believe me, I can sense every sinew, the very tissue and fibre of the soul that millions came to know as James Bigglesworth, or affectionately, Biggles.

The Bigglesworth Adventure Series 1

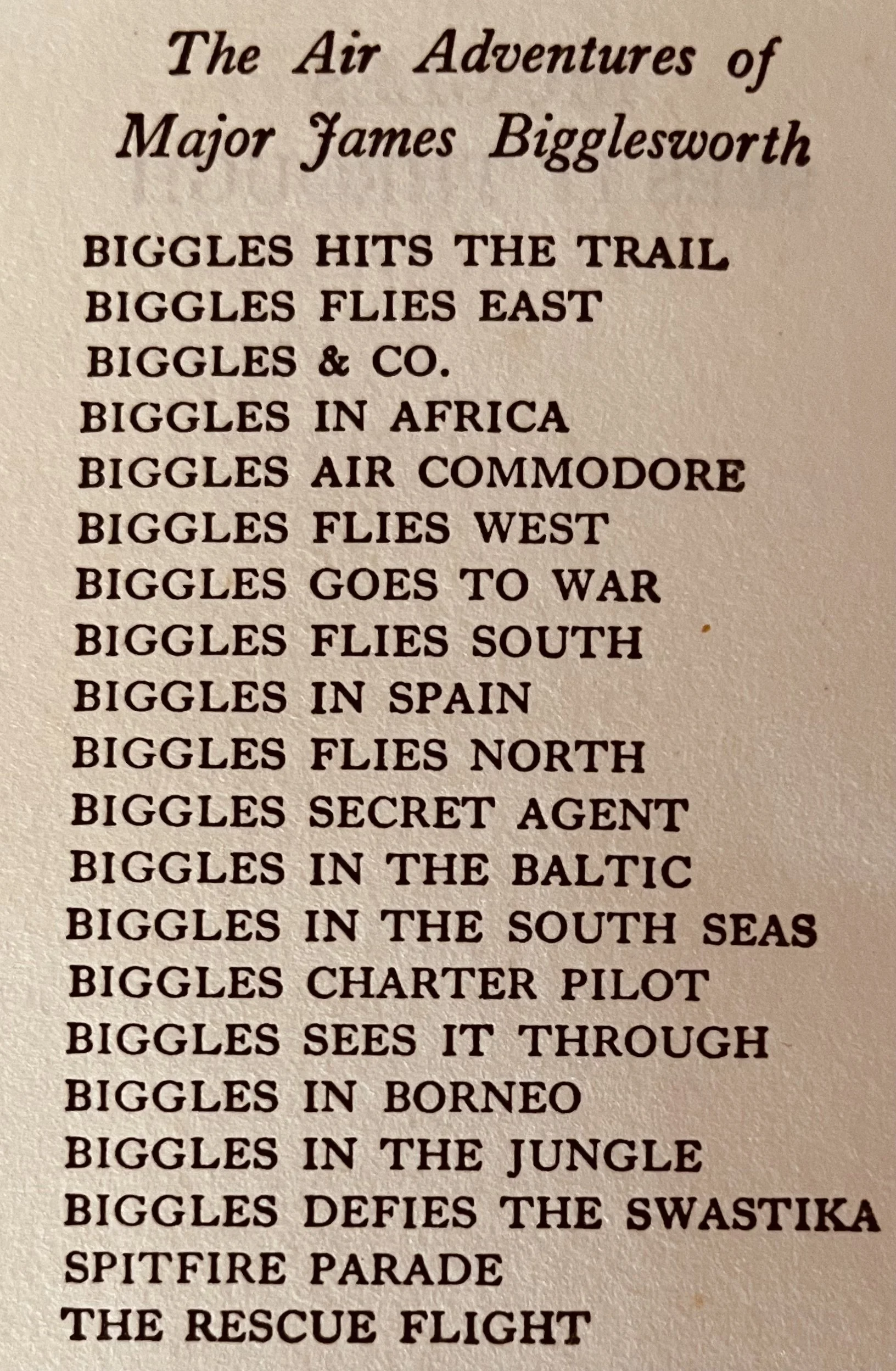

Reading an inside life of ‘Biggles Sees It Through’ first published in 1941, I was interested for find the Adventure Series titles by W E Johns up to this 1951 Reprint.

W. E. Johns has a writing style that immedately identifies his military background, his own flying experiences over the Western Front in the Great War (1914-1918), and which stood out for me when I read the opening lines of Biggles of the Royal Flying Corps. The words in this extract from pages 7-9 are, in a way, timeless. Every aviator whether air or ground, will recognise much here. Certainly, it resonates with my own memories.

Extract ~ pages 7-9

from

Chapter 1

Biggles of the Royal Flying Corps

One fine, late, September morning in the war-stricken year of 1916, a young officer, in the distinctive uniform of the Royal Flying Corps , appeared in the doorway of one of the long, low, narrow wooden huts, which, mushroom-like, had sprung up all over England during the previous 18 months. He paused for a moment to regard a great open expanse that stretched away as far as he could see before him in the thin autumn mist that made everything outside a radius of a few hundred yards seem shadowy and vague.

There was little about him to distinguish him from thousands of others in whose ears the call to arms had not sounded in vain, and who were doing precisely the same thing in various parts of the country. His uniform was still free from the marks of war that would eventually stain it. His Sam Browne belt still squeaked slightly when he moved, like a pair of new boots.

There was nothing remarkable, or even martial, about his physique; on the contrary, he was slim, rather below average height, and delicate-looking. A wisp of fair hair protruded from one side of his rakishly tilted R.F.C. cap; his eyes, now sparkling with pleasurable anticipation, were what is usually called hazel. His features were finely cut, but the squareness of his chin, and the firm line of his mouth, revealed a certain doggedness, a tendency of purpose, that denied any suggestion of weakness. Only his hands were small and white, and might have been those of a girl.

His youthfulness was apparent. He might have reached 18 years shown on his papers, but his birth certificate, had he produced it at the recruiting office, would have revealed that he would not attain that age for another eleven months. Like many others who had left school to plunge straight into the war, he had conveniently “lost“ his birth certificate when applying for enlistment, nearly three months previously.

A heavy hair-lined leather coat, which looked large enough for a man twice his size, hung stiffly over his left arm. In his right hand, he held a flying-helmet, also of leather, but lined with fur, a pair of huge gauntlets, with coarse, yellowish hair on the backs, and a pair of goggles.

He started as the silence was shattered by a reverberating roar which rose to a mighty crescendo, and then died away to a low splutter. The sound, which he knew was the roar of an aero-engine, although he had never been so close to one before, came from a row of giant structures that loomed dimly through the now–dispersing mist, along one side of the bleak expanse, upon which he gazed with eager anticipation. There was little enough to see, yet he had visualised that flat area of sandy soil, set with short, coarse grass, a thousand times during the past two months while he had been at the “ground“ school. It was an aerodrome, or, to be more precise, the aerodrome of No.17, Flying Training School, which was situated near the village of Settling, in Norfolk. The great, darkly looming buildings were the hangers that housed the extraordinary collection of hastily built aeroplanes, which, at this period of the first great war were used to teach pupils, the art of flying.

A faint smell was borne to his nostrils, a curious aroma that brought a slight flush to his cheeks. It was one common to all aerodromes, a mingling of petrol, oil, dope, and burnt gases, and which, once experienced, was never forgotten.

Figures, all carrying flying-kit, began to emerge from other huts and hurry towards the hangers, where strange-looking vehicles, were now being wheeled out onto a strip of concrete, that shone whitely along the front of the hangers for their entire length. After a last appraising glance around, the new officer set off at a brisk pace in the direction of the excitement.

A chilly breeze had sprung up; it swept aside the curtain of mist, and exposed the white orb of the Sun, low in the sky, for it was still very early. Yet it was daylight, and no daylight was wasted at flying schools during the Great War.

He reached the nearest hanger, and then stopped, eyes devouring the extraordinary structure of wood, wire, and canvas that stood in his path. A propeller, set behind to exposed seats, revolved slowly. Beside it stood a tall, thin man in flying-kit; his leather flying-coat, which was filthy beyond description with oil stains, flapped open, exposing an equally dirty tunic, on the breast of which a device in the form of a small pair of wings could just be seen. Under them was a tiny strip of the violet-and-white ribbon of the Military Cross.

… a tall, thin man in flying-kit; his leather flying-coat, which was filthy beyond description with oil stains, flapped open, exposing an equally dirty tunic, on the breast of which a device in the form of a small pair of wings could just be seen. Under them was a tiny strip of the violet-and-white ribbon of the Military Cross.

… but the young newcomer regarded him with an awe that amounted almost to worship.

To a fully fledged pilot the figure would have been commonplace enough, but the young newcomer regarded him with an awe that amounted almost to worship. He knew that the tall, thin man could fly; not only could he fly, but he had fought other aeroplanes in the sky, as the decoration on his breast proved. At that moment, however, he seemed merely bored, for he yawned mightily as he stared at the aeroplane with no sign of interest. Then, turning suddenly, he saw the newcomer, watching him.

End of Extract and by kind permission of Purnell Publishing

The Adventure Series is international. We move through the inter-war years and eventually find ourselves confronting the approaching Second World War.

Many who read this will certainly identify with the descriptive writing. We have been there. We know those feelings. Whether it be an aerodrome in 1916 Norfolk or an R.A.F Base in 2023 in Norfolk, in the quintessential essence of this piece of descriptive writing, nothing has changed, only the century.

What surprised me - and it caught me completely on the hop - I had decided to use audio dictation for the Extract. All was fine until I’m standing alongside the young chap seeing his instructor for the first time. I had to stop a couple of times which answers people’s regular question why I do not make more use of podcasts.

But that’s just me.

This superb photograph is a relief of page 75 FLIGHT ~ THE COMPLETE HISTORY OF AVIATION BY RG GRANT WITH PHILIP WHITEMAN (first published in 2002) revised and updated and republished by DK Penguin Random House, DK London Great Britain 2022, via the Imperial War Museum (IWM). See front cover below.

The Boeing Spearman Kaydett.

The Boeing Spearman Kaydet biplane trainer in service with the US Army Air Corps in 1941.

Life is Good

L.A.C. Kenneth Ernest Webb 1315766 RAF VR on pilot training 1941-1942 Craig Field Alabama.

It was many years before I discovered our Uncle’s photgraph album. It means much because not only did I serve in the police force with the staff number 1104 but I also lived at 110 on the Liverpool Waterfront, being in Liverpool for 14 years.

The informal, relaxed portrait sent back to Britain.

In this, my father’s brother wears the dress tunic of a newly qualified pilot and Senior Aircraftman (S.A.C.)

Upon arrival home, Ken was promoted to Sergeant-Pilot.

The handwriting is his mother’s, Mrs Isabel Alice Webb, using Grandma’s Parker Fountain Pen which I inherited and used for several years until the rubber preished. The pen now lies quietly in the Glass cabinet.

Wings Day April 1941

Kenneth Ernest Webb in the middle with two fellow newly

qualified pilots. Craig Field, Alabama.

Flt Lt H L Payne RCAF Path Finder

The cockpit of the superb Airspeed Oxford twin engine training aircraft

This wonderful photograph is by kind permission of Ms Linda Payne of Canada, the Niece of Flt Lt Payne who went on to become an outstanding Pathfinder with 405 (City of Vancouver) Squadron RCAF and to whom my Mother’s brother, FS Harry Alfred Marshall Pathfinder RAF, was seconded as the Payne Crew Flight Engineer.

Freedom in Two World Wars. A Gentle reminder to me every day. KTW (The aeromodels are made of rough metal, being an SE 5a from WWI and a Supermarine Spitfire from WWII, the latter quite old now as it flew into my room on the Liverpool Waterfront in 2005!) Haha! Alays the romantic!! I’m delighted to say that my two-ear-old nephew has his own SE 5a.

FLIGHT ~ THE COMPLETE HISTORY OF AVIATION BY RG GRANT WITH PHILIP WHITEMAN (first published in 2002) revised and updated and republished by DK Penguin Random House, DK London Great Britain 2022, via the Imperial War Museum (IWM).

19 October 2025

All Rights Reserved

LIVERPOOL

© 2023 Kenneth Thomas Webb

First written circa 2023