Biggles of the Royal Flying Corps ~ An Introduction

Review

Biggles of the Royal Flying Corps ~ An Introduction

I

There is a wonderful bookshop in my local town, Winchcombe. It opens by appointment or at set times and specialises in books from the past, books that are antiquarian, whole sets that cause one to riveted the spot. Spellbound.

Spellbound, I was about eleven or twelve again.

I Turned the Cover.

My goodness! Biggles of the Royal Flying Corps by Capt. W. E. Johns

II

I’d enjoyed reading the Biggles stories as a boy in the early 1960s when they came out each Saturday in picture format; and very soon I moved on to the Second World War. Very quickly, the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), the predecessor to the Royal Air Force (RAF), the world’s first independent air force, faded into memory.

Finding this title, well, what a find. Why so?

Because the accounts disengaged me from 1935 to the present, causing me to recalibrate back 1901-1918, and what a world awaited me between 1912–1918. Not only sophisticated biplanes, but Airships, Balloons and Blimps, the first anti-aircraft batteries, the first searchlight batteries, the first London Blitz and entire industries that are now only an historical note.

I was pulled up with a jolt.

This is exactly the antidote to free up my mind again, to not make such stupid mistakes and errors of judgment, and to also return to enjoying life despite the restrictions we all labour under, wherever we are on this beautiful planet.

Reading this book introduced me to the entire library of Bigglesworth Stories written by Capt W E Johns, himself a First World War fighter pilot in the RFC. It enabled me to understand a little more of the American Boeing Stearman Kaydett Biplane in which my father’s brother learned to fly, before transferring to the larger Harvard monoplane in which he and his friends and fellow student pilots “got their Wings”, and, for the short time that they remained in Alabama - before shipping back to Britain in May 1942 to proceed to their squadrons - permitted to wear the coveted USAAC Wings, eventually in the equally coveted and highly respected SNCO rank ~ Sergeant-Pilot.

Captain Johns has opened up a whole new world to me of what it is like to fly a biplane. They are beautiful. Deep down I knew this, but now their beauty and engineering is enabling me to appreciate that they were, after all, state of the art in their day.

Captain Johns’ authorship is also enabling me to finally grasp a much clearer and very important understanding of the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Air Force. His fictional character follows through in what we call the Inter War Years and of the very brave people who served in it between 1912-1918. We even find him serving in the Second World War.

III

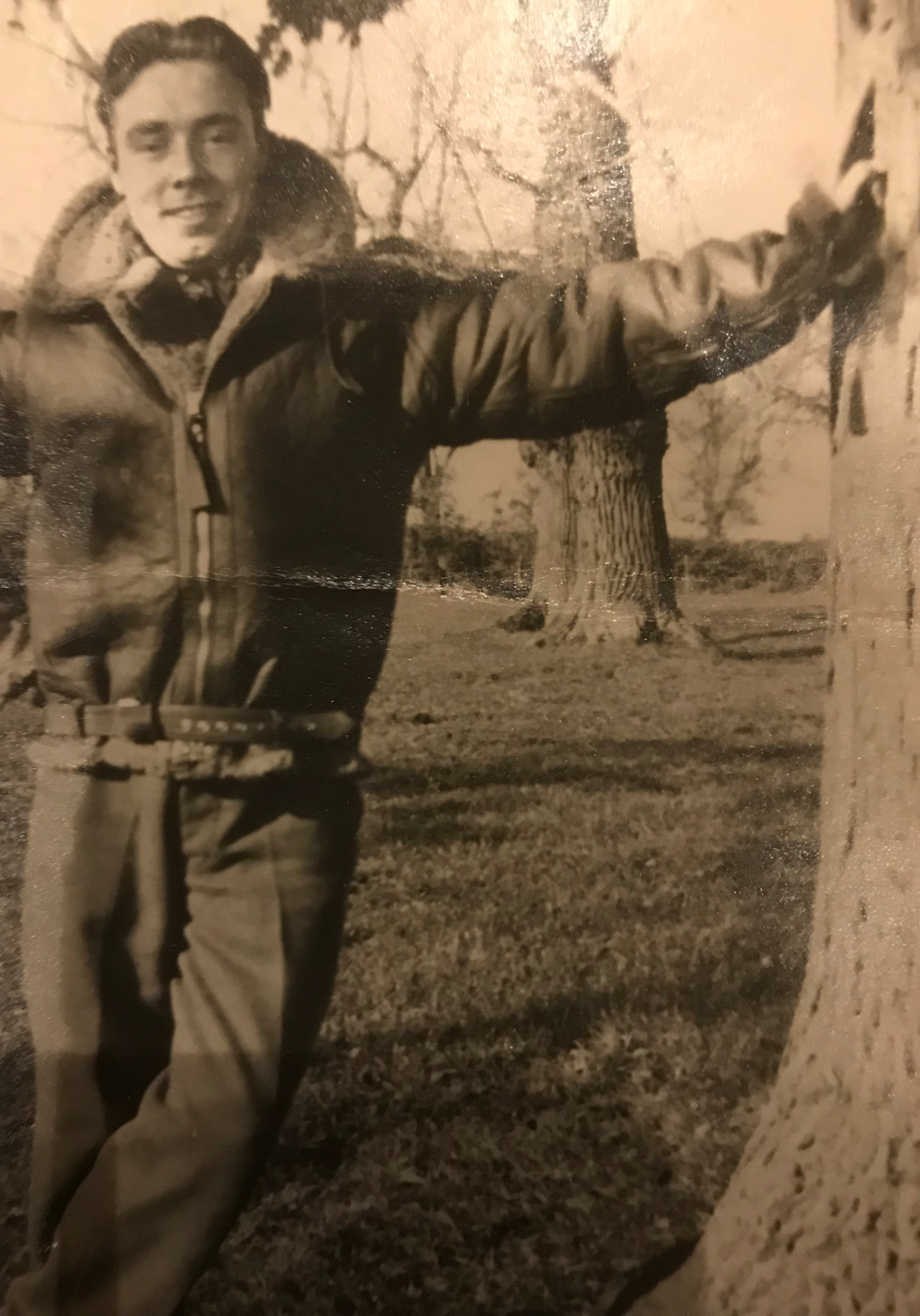

I GREW UP with the Portrait below. I’ve mentioned it many times in other parts of the website.

Only now, 84 years on, do I really begin to appreciate these informal portraits of Kenneth Ernest Webb (1921-1943) … my father’s brother, a Sergeant-Pilot and Skipper of Handley Page Halifax Mark V DK165 MP-E (the Webb Crew) and also of my mother’s brother, Harry Alfred Marshall, a Flight Sergeant Flight Engineer Pathfinder of Avro Lancaster PB402 LQ-M (the Payne Crew).

A book and two people I’d never met yet knew them, it seemed, inside out.

My parents did not want their brothers forgotten. Nor did my four grandparents. All of them also made sure I kept a weather on the earlier world war, now dangerously slipping from importance, and where their brothers too had earned the right not to be forgotten.

IV

It is now, 2025. The world is at its most dangerous. It is a diabolical time, although, reader, do not presume that the use of that noun suggests my alignment with some religious belief. I use it to underscore that in the minds of millions, religion is still the driving force, a belief in things that cannot be seen but which must nevertheless be there. Impatience enters, and I quickly counsel myself not to act upon that impatience.

Initial Flying Training

The world-famous American Boeing Stearman Kaydett Biplane ~ this one being on display at the RAF Duxford Aviation Museum in Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom.

The Stearman Kaydett

This underlines the origin of this beautiful aircraft design ~ the United States of America.

Life is Good! 1941

Kenneth Ernest Webb (1921-1943)

Life is Good! 1944

Harry Alfred Marshall (1923-1944)

V

Extract ~ pages 7-9

Chapter 1

Biggles of the Royal Flying Corps

One fine, late, September morning in the war-stricken year of 1916, a young officer, in the distinctive uniform of the Royal Flying Corps, appeared in the doorway of one of the long, low, narrow wooden huts, which, mushroom-like, had sprung up all over England during the previous 18 months. He paused for a moment to regard a great open expanse that stretched away as far as he could see before him in the thin autumn mist that made everything outside a radius of a few hundred yards seem shadowy and vague.

There was little about him to distinguish him from thousands of others in whose ears the call to arms had not sounded in vain, and who were doing precisely the same thing in various parts of the country. His uniform was still free from the marks of war that would eventually stain it. His Sam Browne belt still squeaked slightly when he moved, like a pair of new boots.

There was nothing remarkable, or even martial, about his physique; on the contrary, he was slim, rather below average height, and delicate-looking. A wisp of fair hair protruded from one side of his rakishly tilted R.F.C. cap; his eyes, now sparkling with pleasurable anticipation, were what is usually called hazel. His features were finely cut, but the squareness of his chin, and the firm line of his mouth, revealed a certain doggedness, a tendency of purpose, that denied any suggestion of weakness. Only his hands were small and white, and might have been those of a girl.

His youthfulness was apparent. He might have reached 18 years shown on his papers, but his birth certificate, had he produced it at the recruiting office, would have revealed that he would not attain that age for another eleven months.

Like many others who had left school to plunge straight into the war, he had conveniently “lost” his birth certificate when applying for enlistment, nearly three months previously. A heavy hair-lined leather coat, which looked large enough for a man twice his size, hung stiffly over his left arm. In his right hand, he held a flying-helmet, also of leather, but lined with fur, a pair of huge gauntlets, with coarse, yellowish hair on the backs, and a pair of goggles.

He started as the silence was shattered by a reverberating roar which rose to a mighty crescendo, and then died away to a low splutter.

The sound, which he knew was the roar of an aero-engine, although he had never been so close to one before, came from a row of giant structures that loomed dimly through the now–dispersing mist, along one side of the bleak expanse, upon which he gazed with eager anticipation.

There was little enough to see, yet he had visualised that flat area of sandy soil, set with short, coarse grass, a thousand times during the past two months while he had been at the “ground” school. It was an aerodrome, or, to be more precise, the aerodrome of No.17, Flying Training School, which was situated near the village of Settling, in Norfolk. The great, darkly looming buildings were the hangers that housed the extraordinary collection of hastily built aeroplanes, which, at this period of the first great war, were used to teach pupils the art of flying.

A faint smell was borne to his nostrils, a curious aroma that brought a slight flush to his cheeks. It was one common to all aerodromes, a mingling of petrol, oil, dope, and burnt gases, and which, once experienced, was never forgotten.

Figures, all carrying flying-kit, began to emerge from other huts and hurry towards the hangers, where strange-looking vehicles, were now being wheeled out onto a strip of concrete, that shone whitely along the front of the hangers for their entire length. After a last appraising glance around, the new officer set off at a brisk pace in the direction of the excitement.

A chilly breeze had sprung up; it swept aside the curtain of mist, and exposed the white orb of the Sun, low in the sky, for it was still very early. Yet it was daylight, and no daylight was wasted at flying schools during the Great War.

He reached the nearest hanger, and then stopped, eyes devouring the extraordinary structure of wood, wire, and canvas that stood in his path. A propeller, set behind two exposed seats, revolved slowly. Beside it stood a tall, thin man in flying-kit; his leather flying-coat, which was filthy beyond description with oil stains, flapped open, exposing an equally dirty tunic, on the breast of which a device in the form of a small pair of wings could just be seen. Under them was a tiny strip of the violet-and-white ribbon of the Military Cross.

To a fully fledged pilot, the figure would have been commonplace enough, but the young newcomer regarded him with an awe that amounted almost to worship. He knew that the tall, thin man could fly; not only could he fly, but he had fought other aeroplanes in the sky, as the decoration on his breast proved. At that moment, however, he seemed merely bored, for he yawned mightily as he stared at the aeroplane with no sign of interest. Then, turning suddenly, he saw the newcomer, watching him.

End of Extract and by kind permission of Purnell Publishing

24 May 2025

All Rights Reserved

LIVERPOOL

© 2024 Kenneth Thomas Webb

Digital Artwork by © KTW unless otherwise credited

First written 23 January 2023

Ken Webb is a writer and proofreader. His website, kennwebb.com, showcases his work as a writer, blogger and podcaster, resting on his successive careers as a police officer, progressing to a junior lawyer in succession and trusts as a Fellow of the Institute of Legal Executives, a retired officer with the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, and latterly, for three years, the owner and editor of two lifestyle magazines in Liverpool.

He also just handed over a successful two year chairmanship in Gloucestershire with Cheltenham Regency Probus.

Pandemic aside, he spends his time equally between his city, Liverpool, and the county of his birth, Gloucestershire.

In this fast-paced present age, proof-reading is essential. And this skill also occasionally leads to copy-editing writers’ manuscripts for submission to publishers and also student and post graduate dissertations.