WßD ~ Chapter 4 ~ Across Town to Elmfield (Revised Edition)

Windsor Street Days

Chapter 4

Across Town to Elmfield

Dark minds are never far

from the candlelight of liberty.

This Third Edition is written as a means of standing with the People of Ukraine in this grim and grievous hour. My thanks to Andrew Fairbrother for the the recording of Faure’s Requiem today.

Part I

FAMILIES ARE affected by the past. The last 107 years stand witness to many wars, and also the two World Wars. Billions of people have lost their lives through these all of these wars.

Of equal standing to the paternal family home - Windsor Street - is the maternal family home - Elmfield Road.

Writing this chapter’s first edition in 2018, I noted that the last four years - 2014-2018 - have followed week by week, often day by day, the four years of the Great War. As a result of an appeal about my mother’s family - her father and uncle - considerable interest has been shown by the local media during the past week. I do not know how this came about. Enquiry suggests that students from the Gloucestershire University working through records, discovered that two brothers had been found in the same camp as German prisoners of war. Their short film (10.14 minutes) part of which the students filmed at my home in 2018.

I wrote a paper for them in readiness and which, therefore, is timely for Chapter Four, and it is as current today, as it was in 2018.

Part II

Two Brothers - The Marshall Family - and a Third Brother

World War I

The Short Film

Section I

MY MATERNAL GRANDFATHER - Frank Ewart Marshall - was born in 1898 and died in 1977 aged 79.

He volunteered to join the British Army during the Great War, and, as the family has always known, and which was confirmed by his youngest son, Frank Frederick Marshall, five months ago, Grandad might have falsified his age.

However, Robert Brunsdon, a military archivist has conducted considerable research for me and produced a superb archive of my grandfather’s war service and of one of his two brothers, Harry or Henry Marshall (depending on which National Population Census one goes by).

Their eldest brother, Frederick Marshall, we know nothing about. His name was always whispered, and Grandad would not speak of him. But he did a very telling action. He and my Grandmother, Martha Isabella Marshall née Hope, nevertheless christened their youngest son - Frank Frederick Marshall. Grandad was not going to allow his eldest brother to be forgotten!

He and Grandma also named their eldest son Harry after his uncle, Harry, died in October 1918 in a POW Camp in Germany. Harry’s nephew and namesake Harry was killed in action over Germany in January 1945.

Both my grandfathers fought in the First World War, both lost their sons in the Second World War.

This happened to countless families on all sides of these evil and totally unnecessary conflicts. Many times, have I wondered how my grandfathers must have thought when they saw another war looming and were powerless to dissuade their sons from volunteering for RAF aircrew in World War II.

Section II

A PHOTOGRAPH taken with fellow soldiers - all of them bearing different cap badges and thus different regiments - reports, at least to me, a young man of at least age 17.

But seventeen is still young.

But as my Grandfather explained to me in the 1970s, a wry smile more in the eyes than the mouth, it was a matter of honour and doing one’s bit, and not waiting to be conscripted; but that neither did one shout or talk about.

However, Mr Brunsdon’s meticulous research quite clearly confirms that, contrary to popular or sentimental belief, age was recognised and those who had enlisted were kept back from the front line until aged 19. This is quite a revelation, for I admit I tire of the number of people telling me we sent fifteen year olds into battle, and so on.

We did not! And I speak now bearing my military rank.

Section III

I WAS a serving police officer and the Area Constable for St Paul’s Cheltenham and which, therefore, took in the maternal family home, 36 Elmfield Road. I also held the Queen’s Commission in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (Training Branch), stationed on the Territorial Army complex off Alstone Lane and which, coincidentally, backed onto Grandad’s original family home, Vine Cottage.

Vine Cottage is still a private residence, and its facade onto Alstone Lane, the whitewashed walls and the timber beams and the mysterious circular window, is virtually unchanged, outside, from when my mother lived there in her formative years, before Grandma and Grandad Marshall, Harry, Tom, Nancy and Frank moved to Number 36.

Mum - Nancy - often recounted the twisting staircase to the bedroom, a cottage with no electricity, a privy at the end of the garden, of the night her hair set on fire when candle wax dropped on her as she was climbing the stairs, and her brother Harry covering her with a blanket.

Section IV

MY Grandparents’ youngest son - Frank Frederick Marshall - was born in 1938 and sadly died only this year (2018), quite suddenly, on Thursday March 29. But my Uncle had a razor-sharp mind, and verified many of the facts and items I refer to in the family archival note that follows.

Anyone doing research into the Great War, and individual families, must keep in mind several factors:

That what we call post-traumatic-stress-disorder (PTSD) today was unknown, and not recognised. Mental health problems emanating from military service too often resulted in courts-martial. Upon demobilisation, the horror of war was not talked about. Keep in mind, too, that in 1918-19, came the pandemic Spanish Influenza which claimed 50 million deaths, in addition to the 40 million lost world-wide between 1914-1918 as a direct result of what we now refer to as the First World War.

In WWII (1939-1945) just 21 years later, this blunt approach to mental incapacity resulting from war injury was dealt with, all too often, by one’s service record being stamped ‘LMF’ - Lacking Moral Fibre - this was certainly so, in the Royal Air Force. It angers me.

That apart from Zeppelin raids on north east coastal towns and upon London, and the sustained ‘First London Blitz 1916-1918’ by the German Gotha bombers - hence King George V changing the family name from Saxe-Coburg Gotha to Windsor - the general public were not in the front line; the tragedy of what was happening in France and Belgium was all too obvious, however, as whole villages, hamlets, towns and cities watched with shock, and a creeping sense of horror, the step-by-step removal of almost an entire generation of men over four years, and a devastating long-term impact on those young men who, mercifully, did survive the war.

That as a result of this, people just wanted to forget ‘the war to end all wars’, and given that the Great War was global, people could not imagine a repeat. Unfortunately, there is no accounting for human nature and its tendency towards violence, depravity and bestiality. They could not comprehend that any future war could exceed that which they had all just suffered. Thus, the inequitable Treaty of Versailles 1919, an act akin to sewing highly productive seeds of discontent, then liberally watering with the most exacting reparations upon Germany. Today, we might liken it to sewing a nuclear device or pandemic into a suicide vest at the other end of the hand-held, or iPhone-operated detonator.

That veterans remained silent. Families gradually settled into a new kind of existence, but, as with my own family - what we now realise was PTSD - was, at the time, seen in my grandfather as merely because he was a strict man, prone to sudden outburst; and yet a loving, doting family man. This dichotomy confused me throughout my life, and only now, as I piece together the jigsaw, that I begin to understand; and also because of my conversations with his youngest son, Frank, until March 2018. Countless families report today, in their own histories, very similar occurrences.

That the total number of military and civilian casualties in the Great War (redesignated World War I once World War II had commenced) was 41 million globally, and Wikipedia reports that there were 18 million deaths and 23 million wounded, “ranking it among the deadliest human conflicts in human history.” Historians generally affirm this. Little did the world know what lay ahead.

That the total number of military and civilian deaths in Word War II is set at 55 million. Wikipedia reports a higher figure of 80 million, if one takes into account war-related disease and famine; but several sources suggest that the figure of 55 million is perhaps conservative, and that globally, the figure might be more in the region of 100 million.

Factor 7 is therefore important when obtaining a correct perspective of factor 6, which suggests that the period 1933-1945 doubled the overall fatality rate of WWI.

Factor 5 is vitally important in order to understand the “thinking of ordinary men and women who had lived through the First World War”, who had lost whole families, and just as they were picking up the pieces and rebuilding their families, they saw the inevitability of an even greater war looming.

Why is factor 9 so important? Simply this. The men who fought in the Great War, who had been prisoners of war, who had been gassed, and so forth - and here I am referring to all sides in the conflict - now saw the inevitability of the loss of their own sons. Many in Germany realised this but could not say so because of the terrifying regime within which they now lived in the 1930s.

Section V

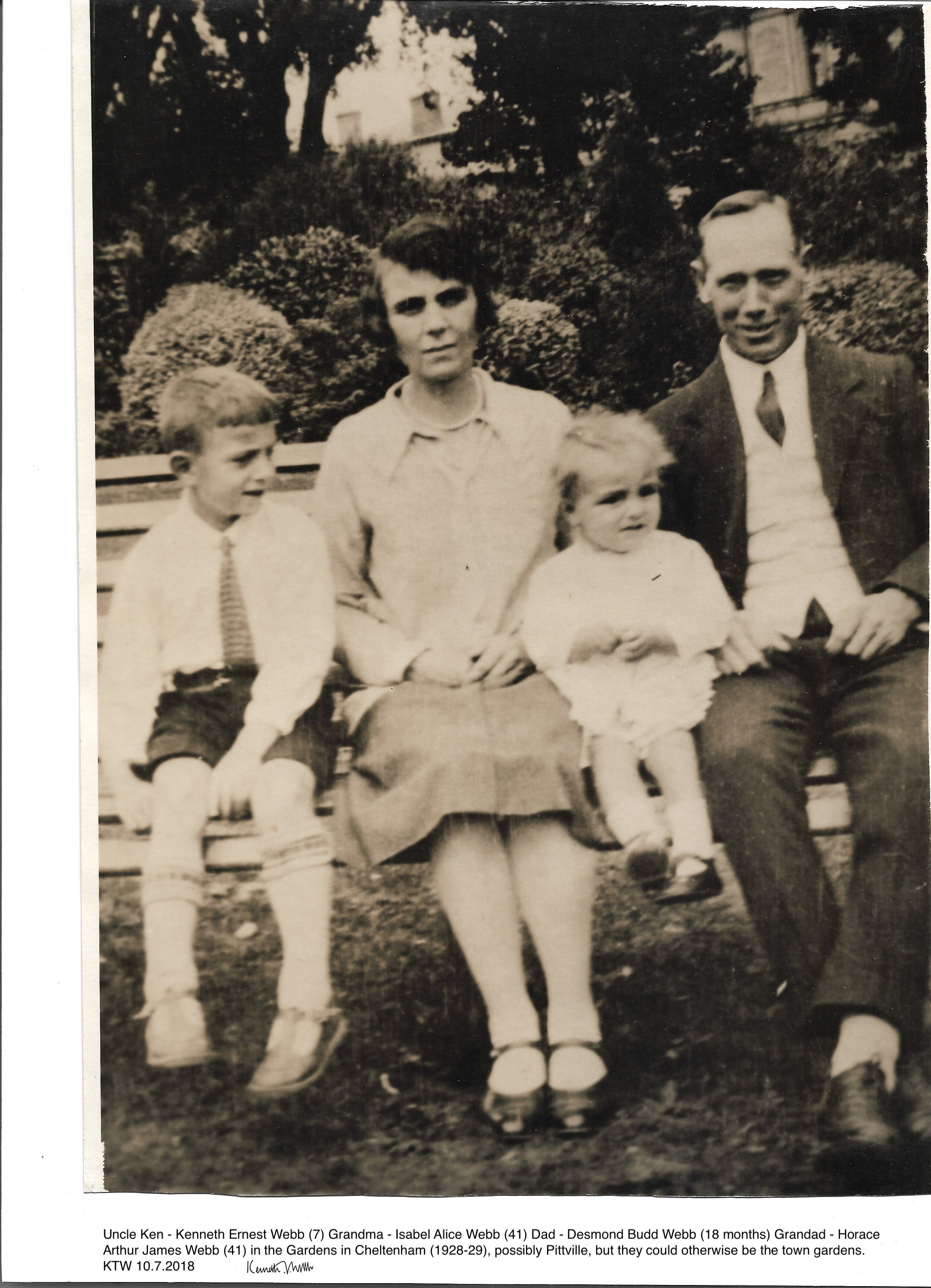

IN my conversations with all four grandparents, this was a constant anxiety. On my father’s side, my grandparents were writing to my uncle not to join the RAF, and repeatedly sending him newspaper articles in support of their concerns, but which Ken rejected briskly in his own typed letters back. These letters are within the family archive. This was the same my with mother’s parents (Marshall) and their eldest son, my mother’s brother, who also joined the RAF.

That both my grandfathers served in the trenches in the Great War, I am only too well aware that they knew, deep down, that they would lose their sons and of course, both did. This can be multiplied by millions, when, ignoring sides, we then cast our eye around the world, and realise that when a population does not keep its politicians and generals in check, then that population will suffer greatly at the hands of those entrusted with power and who will abuse that power, abuse them, and destroy most of them in the process.

Section VI

ANYONE researching the importance of the Armistice in 1918 must anchor this point firmly in their thinking, analysis and deliberation, even though it might actually remain silent on the pages of their dissertation or their Masters.

It is imperative that the 1918 Armistice is not seen only as this singular event, although my concluding notes in this chapter explain this more fully. People hoped that it would be a singular event, of course. But dark minds are never far from the candlelight of liberty.

In writing of the 1918 Armistice, it must be seen through the eyes of those living in 1918 and without awareness of what was to unfold in the next 21 years. History must, at times, stand still so the reader can step back in time and seize that moment of history.

History is not a musty old book, a list of battles and important dates detached from reality and irrelevant to today.

History is the cement in the bricks of life, holding today together.

If we ignore history, we are failing to repoint the cement in the bricks after winter’s onslaught. We flout the lessons of history; we throw them as ripped out pages into the wind. In so doing, we pay a price way beyond that which we can imagine.

Section VII

IN rewriting this chapter, my mind is focussed, because we are at the end of the first week of ‘lockdown’ in the United Kingdom as we prepare for the approaching COVID 19 peak - many like it to a Tsunami - and, strangely, the restrictions now in force help me - for the first time in my life - to comprehend 1914-1919 and 1933-1945.

It is one thing to understand. It is quite another to comprehend. Comprehension does not automatically spring from one’s understanding.

Section VIII

IN 1918-1919 it was perfectly reasonable for people of all countries to rely upon the future being underpinned by the already mentioned eloquent phrase, now one of the sad ironies in the annals of history : the war to end all wars.

No such eloquence occupied the minds of people in 1945.

A sober reality and cynicism set in and which, to an extent, remains.

Having said that, I am thrilled to add here what I have witnessed this week and in the last day as we nationally deal with COVID 19. I limit myself to my own country - the United Kingdom - but am well aware that we see the same in every country hit by this plague - that we pull together, when up against a common foe that endangers all four nations within these islands, we unite as one, and put aside our differences. Those can be returned to in quieter times.

There is unity of spirit, unity of purpose, and a determination to defeat this virus. There is also sober thinking. There is a sense that, somehow, we have reached that milestone, no turning back … life will never be quite the same again.

Nevertheless, those two world wars have delivered Europe, roughly, 77 years of peace - setting aside the Cold War and horrendous Balkan Wars following the death of Marshal Tito and the break-up of former Yugoslavia. So it is understandable when people born in this century cannot connect to the 20th Century. Surely, they reason, peace is a given! Sadly, human nature argues otherwise.

To this century’s generation, it is all around them. The faceless people - old age pensioners - those old people who get in the way in town, who smell, who don’t have a life, who are a nuisance, Gran’s lot, Grampy’s lot, sooner gone the better. I’ll think I’’ be a beneficiary. I mean! Im bound to be!!

But these faceless people still connect

present with past,

the call of duty from the distant past

to the blaring

honk-honk-honk

of the

me-me-me

generation.

Gimme-Gimme-Gimme.

I know my rights.

36 Elmfield Road 1949. The front bedroom upstairs from where my mother (Nancy) on the right below, “watched the street and gardens go up, the gardens all seemed to stay in place mid air for a moment before Grandad threw me under the bed.” I add my mother’s quote for five reasons. Firstly, to give a handle to nephews and nieces 80 years on who might have a ‘non-comprehendo’ moment. Secondly, here, boys, in the lounge downstairs is where Gran (Carol Ann Webb) arrived on that wonderful day on March 30, 1950. Thirdly, 20 years further on is where I used to pop in as a constable for a cup of tea with our grandparents. Fourthly, that same front room downstairs is where your great-great grandfather quietly, and very rarely, opened up to his grandson about his time in the trenches and becoming a prisoner of war which you read about in this chapter. Fifthly, to enable the reader to grasp that seeing houses and gardens go up was world-wide. The civil populations on all sides are the ones who bear the brunt of opposing armed forces. KTW (IBM) June 28, 2021

Grandad (17) Pte Frank Ewart Marshall, the Devonshires … standing behind the seated chap with the tobacco pipe - I look at this, I think of his telling me about the hand-to-hand fighting, and still my toes curl up inside my shoes …

Grandad - Frank Ewart Marshall - what I would give to hear his voice again

Mother and Daughter - my Mum - my best friend - and Grandma - Martha Isabella Marshall

… and the most important photograph of all … Frank Ewart and Martha Isabella Marshall with their first Great Grandson Christopher John - Carol and Roger - in the garden at Nursery Cottage Siddington … and who we next encounter in Chapter Nine … As the Webb Family Motto proudly declares … ‘Life Goes on’ … ‘Das Leben geht weiter’ … with Chris’s Name and in a new Branch … but we are all branches of the same tree … Wonderful! KTW (IBM) 2020

… a quarter century on … still my best friend (2014) - Nancy Webb nee Marshall

a last image … I fell off my seat when I dscovered this in the Archive … It is SO good to see you again Grandma!

Section IX

THIS living connection is fast narrowing and will be gone in a short while.

This is where history’s importance comes into play, and these young people who have a vital role in bringing to the public conscience the lessons that have established our security today, and will, hopefully, secure our future safety, based loosely on the premise - we must never let this happen again.

I was asked how I could be so certain about the horror of WWII.

We are shocked at the sheer magnitude of death, in one day, on the WWI battlefields.

I explained that the answer lies in the statistics. If we take one element of WWII, the Strategic Air Offensive against Germany, Royal Air Force Bomber Command comprised 118,000 aircrew volunteers of which, by 1945, 55,573 failed to return. At the height of the war my father’s brother, Ken, on a 24 hour leave pass home, commented that the average life expectancy at that time - Spring 1943 - “is four ops”. Sure enough, he proved that statistic on 16-17 April. My mother’s brother, Harry, was, in my reckoning, on borrowed time when I count his operations in double figures. And, as night followed day, he too cme to a very abrupt and violent end in a mid-air collision on 16-17 January, 1945.

Thousands were killed on their first operation, or in the very demanding and dangerous OCUs (operational conversion units) while undergoing training. An order from the top for “maximum effort” gave the RAF commanders no option but to commit many of these crews in training to battle.

That only deals with the Royal Air Force. It does not touch upon the losses suffered by the US Army Air Corps, nor the armies, navies and marines of the Allies.

Nor does it report the

millions

of civilians

killed in those

operations.

The losses on all sides is incomprehensible unless we apply the litmus paper test of war being waged in Syria now. Young people, take note. Learn. Act. Do what is right for your country and for your families and for your future. Learn from the past and stop walking around with your eyes closed as if you’ve got a whiff under your nose.

Lewis’s and the Adelphi Hotel in the foreground in May 1941, Liverpool. I’ve chosen this as many years later, my parents’ brother-in-law and sister-in-law became the managers of the Adelphi. Years on, we had a further family gathering there courtesy our friends Andrew Fairbrother and Darren Herbert - a surprise birthday party for me - slight problem, though … I hadn’t seen Mum and Dad for quite a while and, well, let us say, my, then, long hair in 2005 didn’t exactly do me any favours. I was going through my rebellious stage!! That’s what Liverpool does, haha, and why I love my city. My Uncle and Aunt (Pat was Aunt Bette’s younger sister) Pat and Les Freeman, went on to become Mayor and Lady Mayoress of Cheltenham. KTW (IBM) June 26, 2021

Ah dear! “Des, he’s lost the plot. He needs to get it cut. Do something!”

There we are, Mum. Just for you!! Back on track. MD and owner and editor of LiverpoolCity Life 2006-2009

Part III

Section I

So, life at 36 Elmfield Road.

I grew up in the long shadow of that war. I played on bomb sites. I knew all the places in Cheltenham that had been bombed, including my mum’s factory near the railway station and which is now the Lansdown industrial estate. Martins Factory was building parts for gliders, and German intelligence knew this and so bombed it. That is the reality of total war. We were doing exactly the same to Germany.

The glider parts were part of the famous Gliders that would then be towed across the Channel by Stirlings and Halifaxes, Lancasters and the famed Douglas DC-3 Dakota, and the glider pilots would cast off and land at the pre-arranged landing zones, their troops and/or heavy field equipment, and in some cases, both, safely delivered.

What is perfect planning on the planners’ battle plotting tables would, in reality, for thousands, turn into a nightmare last few moments of life, death on a colossal scale … savagery beyond compare. Again, an aspect of total war we easily overlook, heightened by the unwelcome anaethetism that has Hollywood actors walking free from every conceivable situation that, in reality, would have killed the actor in the very first instant.

Section II

GAS LANE ran behind what is now Tesco Superstore, so named as it was the lane that skirted the rear of the town’s Gas Works and which became a target on December 11, 1940 killing 20 and rendering 600 homeless.

Cheltenham’s former Mayor, Councillor Brian Chaplin, in a news interview in 2010 - aged five at the time of the raid - recounts the event vividly:

“I was just 200 yards from the bomb that dropped on the gas holder, which is now JJB Sports, in Gloucester Road. I was in the stoke hole of the Gloucester Road primary school at the time. It blew the doors open and there was a huge orange cloud.”

This raid was on the same night that the Coventry Blitz took place.

It was not until the 1980s that mum mentioned to me standing in Gas Lane with her back pressed against the wall. Only now, piecing together fragments of history and conversational points, I wonder whether mum was caught en route back home from where she worked at Martins in Gloucester Road. Of course, I did not learn of that particular incident, or of her being thrown beneath the bed by Grandad Marshall on another occasion as they watched the street and gardens go up - “the gardens all seeming to stay the same even in the air for just a millisecond” - until, in my thirties, expressing my own anger at the IRA bombings, and rebuking mum, oh mum you don’t understand!

No dear.

Almost a quarter century was to pass before mum told me in depth about these incidents. I then remembered my own arrogance. Mentioning it, mum laughed, “Oh yes, I remember that well, Ken. But you were young and you had your own thinking. Nothing I was going to say would alter your thinking. Each generation has to go through this.”

Part IV

Returning to Frank Marshall and Harry Marshall Snr (1914-1918).

I was in uniform when Grandad opened up, one day when I popped in to my Grandparents for a cup of tea. Elmfield Road was the next street across from Waterloo Street police station … a two minute walk.

I remember Grandad explaining to me how Harry died and that he was with him. Grandad, too, described the nerve-wracking hand-to-hand fighting … ‘them or us, ‘him or me’, Grandad also describing the full length of the .303 rifle when the bayonet was affixed, pointing that it came up above my shoulder, “and you’re a tall chap Ken. I was 6’3 whereas Grandad was 5’8. Then that little, almost mono-syllabic ermmm… …, terrible times Ken. He would then choose silence and would look, as it were, through and beyond some wall.

I remember my toes curling inside my boots visualising hand-to-hand fighting - medieval, literally every man for himself. Kill or be killed. Not exactly the same as dealing with breaches of the peace in the town centre.

Grandad spoke only once about this … I recall clipped phrases, spoken with effort. They whirl in my long term memory but in no order … shouting, screaming, swearing; friends holding tunics of soldiers they were fighting; wrestling in mud, water, fighting back, wriggling free, kicking, grabbing your rifle, not daring to look back; then the next screaming rout.

Both sides experienced the same horror. Kill or be killed.

Recalling these memories, it strikes me today that grandad said ‘friends’, not ‘mates’. This has pulled me up.

Language today is sloppy. Uneducated. Even the waiter’s warmth of welcome at Pizza Express is, none-the-less, of that ilk. A society that has much less sense of self-worth, of duty, of commitment.

Hi there mate. What are you looking for?

Good afternoon. Table for one please.

Sure, mate. Follow me. This table okay mate?

My walk back to Waterloo Street police station was quiet that time. I didn’t mention much of what I now write; my grandfather woud have been ticked off by mum and dad.

Three decades later, mentioning this, my mother’s view was that being in uniform in both the police and RAF VR probably encouraged her father to open up. I’d like to think so.

I mention these factors because these conversations with my grandfather up to his death in 1977, resumed afresh, with greater poignancy, with his youngest son, Frank, between 2016-2018 when my uncle was resolute in his determination that this should be understood, not least because he had personally witnessed in his own RAF service - as part of Operation Grapple - the testing of two British Hydrogen Bombs in 1957-58 on Christmas Island in the Pacific (at that time a British possession) and which thus gave this country its nuclear deterrent.

Part V

Section I

Brief Recap

LET US return to my Grandfather’s and Great Uncle’s war service. The research by Robert Brunsdon (referred to in Part I, Section 3, paragraph 1) has mentioned to me the story picked up by the local newspaper at the time about my great grandmother being charged for the inscription of the headstone ‘Asleep in Jesus’.

This came about during his research on my family’s behalf.

Mr Brunsdon writes:

By the way - the assertion in the newspaper article

that the family were charged for the wording on the headstone is a myth.

When the plan to allow personal inscriptions was first put forward,

civil servants formulated a scale of charges based on an amount per word/letter.

Once it got to final approval stage that idea was dropped.

Unfortunately the forms had already been printed, so reference to the charge remained on them.

A covering letter (or slip of paper included in the envelope) explained the situation,

but that is usually lost by relatives.

Hence the myth of charging for the wording.

I quite understand how this happens. Even our own family archive throws up anomalies. That is par for the course.

So, my view is that I fully concur with Robert Brunsdon’s explanation, and the family is most grateful.

Section II

Provenance

I have custody, on the family’s behalf, of the brass tobacco tin that was issued to all soldiers in 1914-1918, designed to keep things dry underground in the trenches. I also have the large round ‘Penny’ with Harry Marshall inscribed thereon. My grandparents kept this on their fireplace. Over decades of cleaning, the name is beginning to disappear, so all items are now in the Marshall-Webb glass cabinet or in the RAF presentation cabinet. Other accoutrements from the Great War are also held; a three-sided brass matchbox holder, a brass cigarette case for keeping the contents dry, and other things too.

But this is where facts begin to fuse. Why?

Because some of the items belonged to my paternal grandfather, who was also serving in France at the same time as mum’s father. This will be the same for countless families.

The one thing I can be certain of is their provenance as items used on active service, issued to my grandfathers and/or great uncles ~ seven men in all. What I cannot guarantee in every case is “who owned exactly what?”

Let me give one example.

The stirrups I have, I know most certainly belonged to my paternal grandfather, Pte Horace ALbert James Webb ,as he was on horseback at times during his service in France. It is his image that fronts Windsor Street Days; the stirrups are those that he is wearing.

But can I affirm their provenance?

Well, I can, in so far as I remember them at the paternal family home, 25 Windsor Street. So, did they belong to Horace? Here’s where provenance steps in.

Well, I cannot say for sure, because there is no marking on them or on the chain mail that held them in place beneath the boot, with the leather strap holding same in place above the boot, because, for all I know they might have belonged to Horace’s father-in-law who served as a Breaker of Horse - and noted for that skill - in the Indian Army four decades earlier. Then again, I could go back further still to his father’s service in the Crimean War 1854-57 (my grandmother’s grandfather).

Provenance is a hazardous path that zig-zags generations and bloodlines. And provenance must be exact if it is to be reliable.

The type of Lee Enfield .303 Rifle issued to British and Empire Troops in the First World War.

This image is kind permission of the Australian War Memorial

Section III

The Scotch Corner Incident

I now come to a separate recollection. Again, it is as if the conversation were but yesterday. One might wonder how one can recall conversations in such detail half a century on. I ask myself this too. Put simply, I am a police officer (retired) of 11 years standing, and a lawyer (retired) of 36 years standing, as well as military service that ran alongside those careers of 21 years, and the first two required the discipline of making accurate contemporaneous notes and statements of evidence, in which we were taught to recall detail and to leave nothing unreported.

Scotch Corner came up in one of our conversations. I was going up to Yorkshire on police training, and mentioned I was having to go through Scotch Corner.

Oh?

Yep. Scotch Corner. Do you know it then Grandad?

Oh aye. I know it alright.

But not that one.

I know that too.

But I’m talking about the one in France.

Oh right! How do you mean, Grandad?

It was a crossroad of trenches;

those damned trenches.

Nothing but mud.

Muck, bullets, filth, bodies,

stench,

wiz-bangs overhead,

and water.

Always water.

Loads of brown muddy, filthy water.

Ankle deep.

Can’t stand the stuff!

We used to go to the front each day and we’d pass Scotch Corner.

A young Scots lad had ‘bought it’

and he was lying there

in his kilt and sporran.

And each day we’d all sing out,

‘hey Jock’, ‘Morning Jock’,

and each evening we’d say it again,

‘Hey Jock’, ‘Evening Jock.

Been bad today but we’re still ‘ere’.

Was sad.

As each day passed

we could see young Jock

getting

deader and deader,

if you know

what I mean.

Mum says you’ve seen a post mortem?

Yes, Grandad. God, I didn’t like that.

One of them passed out.

And when they pulled it all back,

I kept thinking,

‘no, surely not, surely not Grandma Webb …’

Yes. I understand.

Have a chat with mum and dad.

Well, we had to push on.

We had to take the line.

We knew where they were.

We could ‘ear ‘em talking.

No-Man’s-Land wasn’t as wide as you think.

The officers were getting us all ready;

we fixed bayonets and the worst part was the waiting.

A huge artillery barrage over our heads to soften ‘em up.

But what we dreaded was the whistles.

Then it was up and over

and every man for himself.

Not good. Not good, aye.

At this point, I remember Grandma came in with a pot of tea.

Grandad loved his tea and he loved having everything neat and tidy and in its right place.

Grandma sat down and returned to her knitting. Grandad was sitting forward on the settee, his preferred place and I was sitting on a stool by the fireplace. He always sat forward with his arms on his knees as if warming his hands. I’ve seen many photos of this posture in trench warfare.

But we must put the record straight on this point, because his son Frank explained to me in 2017 that the whole family used to sit like this round the fire at Vine Cottage. It’s what people did in those days.

After a while, chatting generally about current things, the family, my police work, my health, my RAF/ATC service, Grandad continued …

Well, we got caught out.

They got round the back of us somehow.

We got cut off and we were captured.

We were being marched back

along our trenches now in German hands,

and this guard,

he was a decent chap actually,

saw young Scottie.

He halted us and went up

and liked the look of the Sporran.

A war trophy. Ermm.

Some war trophy that turned out for ‘im!

Aye!! I remember his big kettle helmet;

nothing like ours.

He bent down and took hold of it,

and of course Scottie was now empty, like air;

and his carcase just caved in

and a whole blast of dust

came up at that guard.

It plain shocked him

and he staggered back.

So much so, that when we saw him next morning,

his hair had turned white overnight.

So that’s Scotch Corner.

Section IV

Prisoner of War Camp

ROBERT BRUNSDON’s research into the Official War Diary of the Gloucestershire Regiment - and also possibly the Devonshire Regiment - enables me to report on the battle in which my grandfather was engaged when he was captured.

I was under the impression from what my grandfather had reported, that it was two years since he had seen his brother, and that he had presumed that Harry was dead. And as time wore on, the family, generally, assumed that Frank Ewart Marshall had been a prisoner of war for two years.

What I do know is that someone told our grandfather that they thought that his brother was in the camp ‘hospital’.

Our grandfather was always quiet when he spoke about this; this was the 1960s-70s : of dismantling empire, of stoicism and, in British people, an unwritten code of conduct that required emotion to be suppressed, and largely remained so even into the mid 1980s.

By 1990 the term ‘respectable society and common decency’ had rapidly declined, an object of ridicule.

In its place stood a new, alien, aggressive and disrespectful form of expression to at least three generations in their 50s-90s.

And so it is today, even whilst the Covid 19 Pandemic is about us all.

Our Grandfather intimated that his brother had died in his arms.

I remember Grandma putting her knitting down; she was upset. Not outwardly. But I’m certain that Grandma would have been thinking of the loss of their eldest son Harry, the loss of their younger son Tom in a drowning accident, and the loss of their two daughters in infancy.

Stoicism stepped in, and the teapot found its way to the kitchen.

Mum’s parents shouldered on, as had Dad’s parents 15-20 years earlier.

Harry Marshall Junior wrote to his parents in January 1945, expressing relief that the snow has at last gone from his RAF Station (Gransden Lodge) in Cambridgeshire, summing up our grandfather’s disdain for mud - which was the case until his death in 1977:

“… you had better get some practice in Dad.

Well all our snow has gone.

I am glad too.

It’s so messy with it all about.

Nothing like dry road aye dad.”

… nothing like dry road. That says it all.

It bridges the great chasm between the Armistice 1918 and which we now know as the Act of Remembrance.

Today, in the armed forces, whether serving or retired, we tend to refer to the Act of Remembrance as The Armistice, not even Armistice Day. It is The Armistice. To do otherwise seems disrespectful :

to the signing of the Armistice

at the Eleventh hour on the Eleventh day,

in the Eleventh month of the year of Our Lord,

One Thousand Nine Hundred and Eighteen.

Chapter Four ~ Part V

AS I’VE mentioned in this recollection, fighting at the point of a bayonet is something that cannot be fathomed. Its modern comparison might be the terrifying knife crime that has large parts of our major cities in the United Kingdom, and around the world, gripped in sudden lawlessness, and with a police force in this country that seems inept. In my police service in 1970-1981 it was unthinkable to have ‘police-no-go areas’, areas where the police had been driven out. Within ten years that had changed. To give an instance.

Cheltenham, during my service, had six 24/7 area police stations in addition to Northern Division HQ, and next door to it, County Police HQ. Each area station was staffed by a sergeant, an area constable, and four police constables on rotating car shifts. This was the template for every town and city in Gloucestershire. It was mirrored in every constabulary throughout the United Kingdom. Shift Command of all six Areas lay with the Shift Inspector at Cheltenham Central (Northern Division). The shift Inspector also commanded the Northern Division operations room which was staffed by a Station Sergeant, two Patrol Sergeants, a radio operator and the constables in charge of Cells (as they were then called). Again, the Central Shift was 24/7 with five constables, each allocated one of the five foot-beats in the town of Cheltenham itself.

The public complained, nevertheless, that they never saw a policeman. I look back now and smile. We were all over the place! We also commanded respect. When we walked the beat in the towns and city centres, we were a very definite and appreciated presence. All of that has long since gone. How so, one might ask? Following the 2008 Economic Crash, the terrible austerity measures introduced, saw the national police strength drop by almost 200,000. In my last year, 1980-81, I was posted to Stow-on-the-Wold, high up on the Cotswolds. I loved it. We had a similar strength to that of Cheltenham, except that in overall command of this sub-divisional station we had a Chief Inspector in addition to the Inspector.

In 2017, at an incident on the A40 running over the Cotswolds, the two traffic police officers explained that they covered Gloucestershire. Then a second vehicle arrived. Who are you, officer? I’m from Stow. Oh, right. My old station. You were at Stow? Yep. When? 1980. Oh God. I wasn’t even born. No. None of you were. But I’m intrigued. How many of you are at Stow? Me. You? Yep. Little-ole-me. I cover the whole of north Gloucestershire.

Those three constables could not quite grasp the police force of my day, of my father’s day. To them, its strength alone suggested to them ‘shangri-la’. They simply could not comprehend the system.

If you’re puzzled by all this and you’re in the UK, think ambulance, think five hour response times to 999 ambulance calls, and I think you’ll get the idea.

*

I write Part V at the moment that an autocratic despot, Vladimir Putin, will possibly lead the Russian People into the biggest land war since 1945, with his invasion of Ukraine.

Ukraine is two and a half times the size of Great Britain.

This, therefore, is no ‘little local difficulty’.

These are the exact same tactics of bullying and coercion adopted by Adolf Hitler, in 1938 with Czechoslovakia, in 1939 with Poland, in 1940 with what became Occupied Europe, and then on June 22, 1941 his invasion of Russia.

The Donbass Region seeks secession. It is Russian-speaking. This morning, Sunday February 20, 2022, we see the third day running, provocation by the separatists against Ukraine, the deliberate destruction of a gas pipe line by explosion, and an artilllery barrage that attempts to bait the Ukraine Armed Forces to return fire, which would play into the hands of Putin and Lukashenko to invade simultaneously from the east and the north. The Ukraine Armed Forces have not taken the bait.

When the invasion commences, the battle will be horrendous. And people should understand exactly what is at stake. This is a potential war that dwarfs the Balkan Wars involving Serbia, Bosnia, Croatia and Kosovo.

The Russian People will be faced with thousands of their own being returned in body-bags. It will be bloody. It will be at the point of a bayonet.

Because, even today, that is how our armed forces are taught to fight should we come into direct face-to-face contact with the enemy. It is horrendous. It is vile. it is obscene. It is also replusive, when one considers that Putin and Lukashenko will be in no personal danger at all.

On the battlefield it is kill or be killed. And I am well aware that if I were still in military service and finding myself in this predicament, then I would kill, I would be ruthless, not with the civil population, but with my opposite number on the battlefield, because I am not going to be put down by people who have no thought for the Rule of Law and of Peace and of Democracy and of Freedom.

And I am very aware that even though my grandfathers did not want to do it, nor my four uncles in two world wars, it had to be done. That is the price of total war. That is what happens when despots and autocrats get their way. it ends in horror and bloodshed and their eventual defeat but at the price of millions of lives.

In 1940, we saw what Hitler did in his Blitzkrieg launched on May 10. I quote from a superb study FINEST HOUR by Tim Clayton and Phil Craig. Let me set the scene. British and French Forces are in full retreat to the French coast and to Dunkirk and Calais.

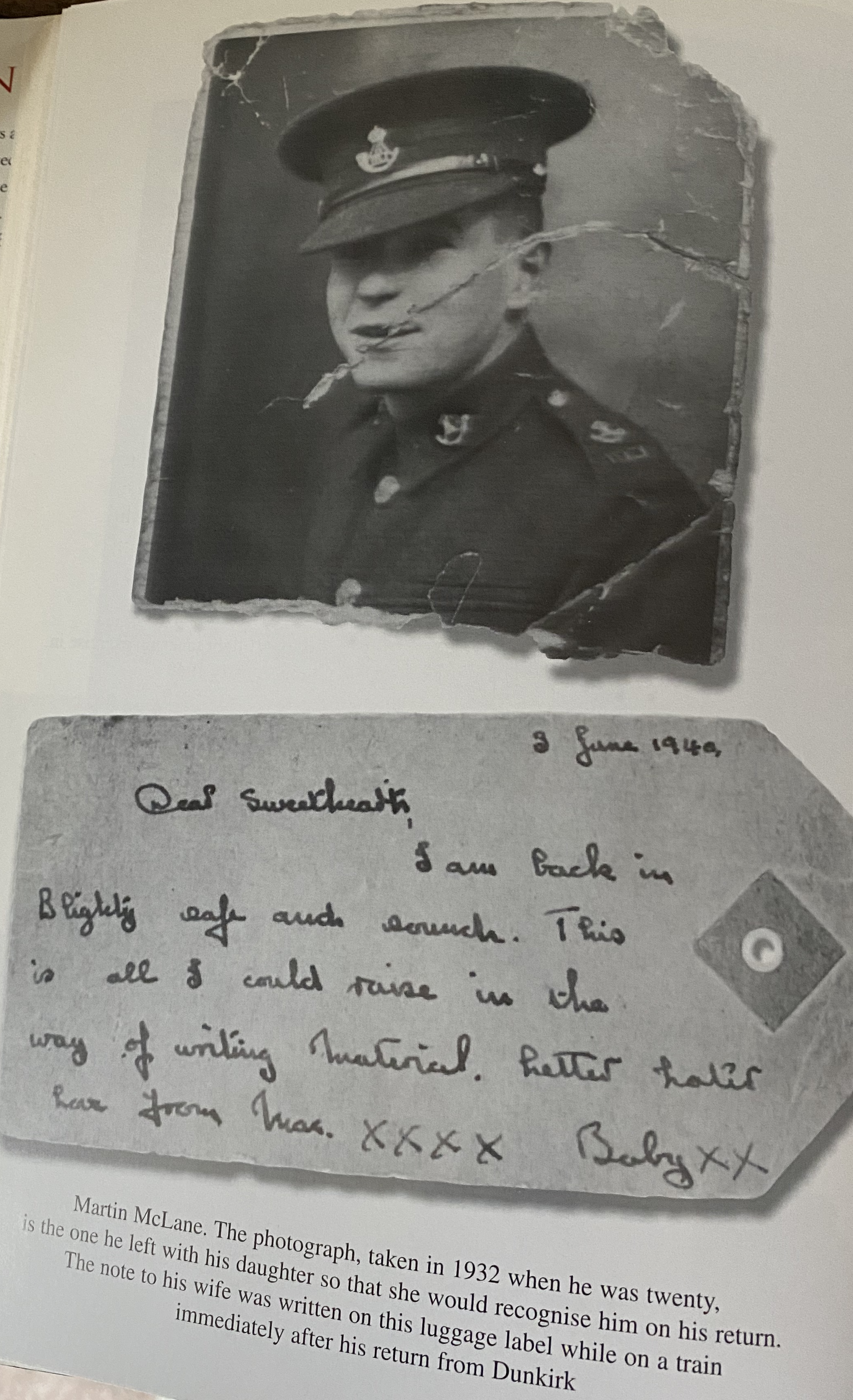

On page 94, Platoon Sergeant-Major Martin McLane, 28, 2nd Battalion, Durham Light Infantry, originally stationed in Nomain near the Franco-Belgian border, comes across a scene of battle just fought.

A short way beyond St. Floris they ran into other members of their battalion. It was ‘C’ Company, or rather what was left of ‘C’ Company.

‘I found the storeman called Rutherford walking across the field picking up the rifles of the fallen. And all around was blood and the debris of a bayonet attack. By then they’d lifted up some of the wounded, but there were dead people lying there, both Germans and British, all over the place. When you see the blood and the mess and the gore after a bayonet attack, nasty. They had driven them [the Germans] back to the line of the railway.’

He was looking at the bodies of two Manchester machine-gunners. Their faces were horribly contorted. McLane picked up a dead German’s rifle and found about thirty rounds of ammunition in the former owner’s pouches. He had given his own rifle to a soldier who had none, but he preferred to have something a bit more powerful than his revolver. He was feeling very subdued. Some of the bodies he had just seen were men he’d played rugby with a few weeks earlier.

Need I say more?

But let there be no doubt. If Russia invades the Ukraine, then we are entering the opening stages of what history will, in time, record as the opening stages of World War Three.

Company Sergeant-Major Martin McLane (28) at the time of one of the many bayonet attacks in 1940, this photograph taken of him eight years earlier in 1932.

Part VI

Conclusion to Chapter Four

IN REVISITING this Chapter Four, I write with a heavy heart, even though when I first wrote this chapter I sensed being given a huge and distant privilege by family and ancestors alike, long departed.

In Part V I am compelled by events to write into this part of my Windsor Street Days.

To the family, I say this. Windsor Street Days are also my story; it interweaves the longer family account. It is my way of doing things, and I will not be gainsaid. The First and Second Editions laid the foundation stone of the family story; but I have my own story to tell too, a life that has been rich and varied, comprising four professions, and my life started at Twenty Windsor Street, and it is Windsor Street I frequently drive along these days, too. It gives me my bearings.

And that is an end to the matter. We all know the famous ‘ktw hand-up which says, no; that is an end to the subject, it is not for discussion. And I’m certainly not going to change my ways.

To readers, my family tend to criticise my “military bearing” as they call it.

It is not so much military bearing as an ability to carry oneself and to be aware that when in formal dress, such as a suit and tie, one conducts oneself accordingly and tries best not to emulate a sack of potatoes … something the Z Gen are rather good at, and which the ‘oldies’ are all now trying to copy before it is too late. This has its roots in disciplined service, but actually more in almost thirty years as a junior lawyer practising probate, succession and trusts.

I say this.

Be proud of who you are.

Stand up for what you believe in.

Do not be kowtowed by anyone.

Live and let live.

And stop taking for granted the freedom you enjoy. It has been paid for at a price beyond measure.

And this is always how freedom is bought. Freedom does not come free. It has to be paid for, and then guarded jealously, as the People of Ukraine have discovered when they had the courage to depose their autocratic leader, then withstood Russia eight years ago when it seized the Crimea; they stood their ground and established a Sovereign Nation State.

Part III records verbatim conversations.

Grandfather and grandson had several of these conversations, but that reported here, especially of the Scotch Corner Incident is as clear today as the day we chatted about this. This would be in the summer of 1973 when I was about to commence my Continuation Course as a probationer constable. Dishforth RAF Station had been requisitioned and assigned to the police service, even though, to all intents it appeared a fully operational Royal Air Force station.

Recalling my grandfather’s description of going over the top and Robert Brunsdon’s research into the Redoubts caused me to rethink.

Grandad made no mention of redoubts. He talked of being cut off, of German troops coming round the back, effectively encircling them.

The redoubts were positioned to hold the line in front of them.

If the line gave way and retreated, it was the task of these redoubts to hold their positions for around five minutes, giving the front line the opportunity to reach the rear line, whereupon they would signal to the redoubts to also turn and make a headlong dash to the safety of the rear line under protective covering fire.

But in the heat of battle, confusion, and so forth, the redoubts did not receive, or missed, the order to abandon the positions.

I say this because it makes me realise that our grandfather’s recollections would have been of many situations, perhaps over days, or months.

With time, everything is fused into one. The reason I say this is that I cannot see a situation where soldiers holding redoubts would be waiting for the whistles from their officers to go over the top and charge the German front line.

These must, therefore, be recollections of separate incidents.

As with everything, even in battle, the order of the day must be :

Provenance not Conjecture!

I am very sad today when I realise what faces us. Music, as always, helps us to best express our inner feelings and so I am grateful to Andrew Fairbrother for sending me Faure’s Requiem this morning. Its YouTube clip can be viewed here. Thank you, Andrew. You are such a good friend. Hold firm, and let us talk again, soon, of times on the docks, our coffees and the shared ciggies ~ in the good old days. Ken

Kenneth Thomas Webb

28 May 2022

All Rights Reserved

© Kenneth Thomas Webb 2022

Rewritten 28 June 2021

Ken Webb is a writer and proofreader. His website, kennwebb.com, showcases his work as a writer, blogger and podcaster, resting on his successive careers as a police officer, progressing to a junior lawyer in succession and trusts as a Fellow of the Institute of Legal Executives, a retired officer with the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, and latterly, for three years, the owner and editor of two lifestyle magazines in Liverpool.

He also just handed over a successful two year chairmanship in Gloucestershire with Cheltenham Regency Probus.

Pandemic aside, he spends his time equally between his city, Liverpool, and the county of his birth, Gloucestershire.

In this fast-paced present age, proof-reading is essential. And this skill also occasionally leads to copy-editing writers’ manuscripts for submission to publishers and also student and post graduate dissertations.